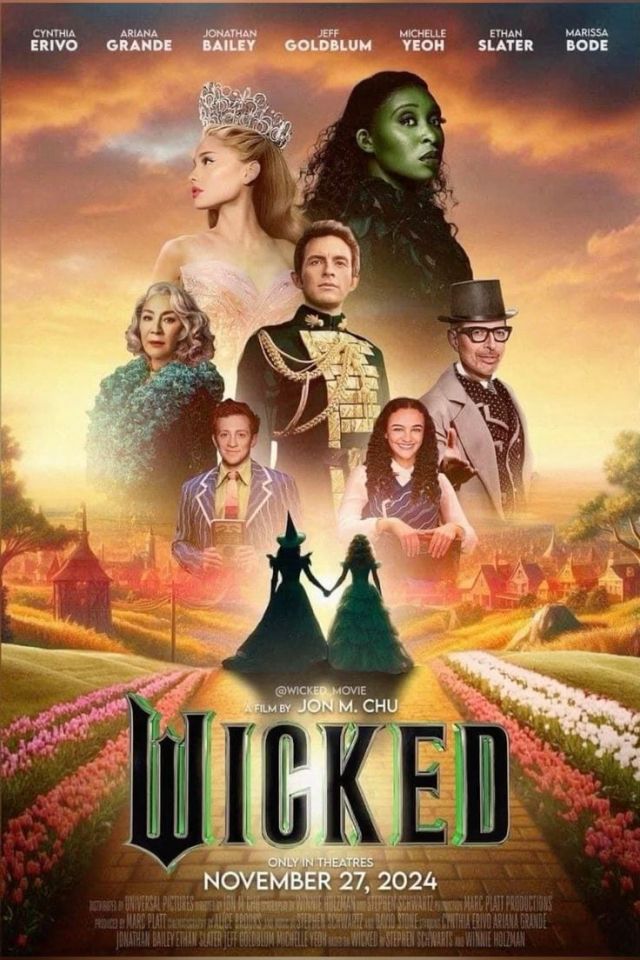

When adapted for the big screen, Hollywood’s trend of breaking books, plays, and musicals into Part I and II is hard to see as anything more than a ploy to get audiences to pay twice for a complete story. Dune, Twilight, Harry Potter, etc. All these films represented stories broken in half to allow for longer films. The audience does get more film overall, but at what cost to the story? The trend continued in November with the release of Wicked: Part I, which hadn’t been widely marketed with the Part I moniker per the gallery of posters below. Only one of these has Part I listed.

Perhaps it stunned others in the audience to see this two-and-a-half-hour movie tagged as Part I based on a Broadway musical with a total show runtime of two hours and twenty minutes. As someone who went into the film without seeing the staged version, which might be the case for many audience members, there weren’t any reference points for comparison. And as the musical numbers went on, and the plot tried to get into gear, the movie’s length weighed down the whole experience. By the time the climax arrived with Defying Gravity, I just wanted the movie to finish. The length and truncated plot structure ruined a tremendous musical number sung by a fantastic actor.

The main issue with how they chose to adapt Wicked, the Broadway musical, into Wicked Part I is that they didn’t account for what happens when you break a story in half and don’t adjust plot elements to ensure each half of the story feels complete. By making Part I simply Act I of the musical, and without adding any substantive changes, the character arcs end up underbaked, and it emphasizes the wrong plot elements, which do not matter as much in the climax. The creators did this while adding more than an hour of additional run time compared to the staged version. If others noticed the slow meandering of the plot, this is a critical reason why.

This essay is not a critique of the performers, the musical numbers, or the film quality. I rather enjoyed the performances, though the sound mixing of the emotional songs (especially The Wizard and I and Defying Gravity) placed the instrumentation too far into the foreground for my taste. However, I do want to analyze what happened to Wicked’s plot by breaking the story into parts and where all that extra time went.

Part I additions/differences in plot elements

With the film as a guideline, it’s hard to imagine how the playwrights fit all of Act I into an hour and twenty-five minutes for the staged version. Upon watching it, the phrase that came immediately to mind is ruthless efficiency. The Broadway musical moves with machine procession in its use of time and pacing. Yes, this partially has to do with the difference in mediums. It has actors on a schedule, musicians, stagehands, all on the clock. This means that any examples of the stage show falling short on plot are forgivable, to a degree, due to the breakneck pace it sets. There isn’t time to analyze plot as the next scene is already upon the audience.

An exhaustive list of the difference in dialogue and staging between the two versions of Wicked seems reductive. However, there are four instances to highlight where the film deviates from the script of the original production that give insight into what happened with the plot of Wicked Part I.

Addition one: young Elphaba

The first addition from the staged version is a short sequence during the intro song “No One Mourns The Wicked,” in which a young Elphaba and her sister are introduced. We get to see how Elphaba is made fun of by the other children, that she has a latent magical power, her protective nature towards her sister, and it establishes her bear caretaker to reinforce Elphaba’s love of the animals. Altogether, this added scene runs a total of 00:01:42 and is perfect for setting up all the elements listed above. It is efficient in how much heavy lifting it does for the plot—no complaints with this addition.

Difference one: intro to Shiz

The first difference to note between the staged and film versions occurs as the characters are dropped off by their parents in the courtyard.

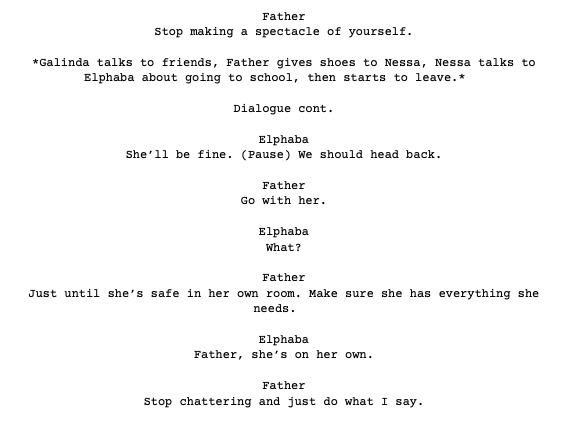

In the play, this is how the dialogue plays out after Elphaba goes on her defensive speech about being green:

The same scene in the film plays out rather differently:

The change might seem subtle and missable if you’re not paying attention. However, the act of changing the introduction of Elphaba to Shiz from knowing she is attending to not knowing changes her character arc.

In the play, Elphaba arrives at Shiz knowing she will be a student, and while she is there only because her father is worried about Nessa, the audience can assume that she will hone her magical skills. It is never explicitly stated in the play, but the act of attending the school allows us to see how getting there and interacting with Ms. Morrible is part of her arc. When it is discovered that she has these inherent magical powers, Ms. Morrible says she will teach her, and this might allow her to see the wizard. Queue The Wizard and I.

In the film, Elphaba comes with them to say goodbye and help carry luggage? It’s not immediately clear why she came with them or why the father, who we know despises her, wanted her to come. Furthermore, when Elphaba says, “Father, she’s on her own,” in response to the father wanting her to go with Nessa, this reinforces the fact that Elphaba isn’t expecting to or even desirous to go to Shiz. It begs the question, what does Elphaba really want? What is her desire as a character? The audience soon learns through the lyrics of The Wizard and I:

When I meet the Wizard

Once I prove my worth

And then I meet the Wizard

What I’ve waited for since, since birth!…

And one day, he’ll say to me

“Elphaba, a girl who is so superior

Shouldn’t a girl who’s so good inside

Have a matching exterior?

And since folks here to an absurd degree

Seem fixated on your verdigris

Would it be alright by you

If I de-greenify you?”

And though of course, that’s not important to me

“All right, why not?” I’ll reply

Elphaba tells us she’s wanted to meet the Wizard since birth. One, because he won’t be small-minded and bigoted toward her green skin. And two, she wishes for him to use his magic to de-greenify her. Here, we get a glimpse into what Elphaba wants. She wants freedom from the bigotry of the people of Oz. In the film version, how does she expect to meet the wizard? If she didn’t get into Shiz, what is her plan?

Even with this difference, the scene could have worked if Elphaba tried to convince her father to let her join Nessa. If he told her it was time to go, they needed to let Nessa alone, and Elphaba replied, “Shouldn’t I maybe stay to help her get settled and make sure she’s alright?” It would reinforce the childhood scene of Elphaba’s protective nature of her sister, and it gives her agency in that she wants to attend Shiz.

Both versions would have helped Elphaba’s character arc if she’d also wanted to study with Madam Morrible. This would have made Galinda’s and Elphaba’s goals at the university the same: learning from Ms. Morrible. Elphaba would want this as a way to meet the Wizard. Galinda, let’s be honest, just wants to be famous. But this alteration would better suit their rivalry. Instead, Elphaba is magically gifted from birth and mentored by Morrible. It doesn’t make her an active driver of her wants/needs.

Addition two: training with Madam Morrible

Jammed between the bloody chalkboard scene with Dr. Dillmond and the meeting of the animals is a scene depicting a lesson by Madam Morrible with a levitating coin. Elphaba isn’t having much luck until she is pushed by Madam Morrible, asking questions about what happened to Dr. Dillmond. Elphaba reacts by shooting the coin into a clock through her strong emotional connection to the animal’s plight. Madam Morrible says, “Once you learn to harness your emotion, the sky is the limit. It could lead you to the Wizard himself.”

This new scene, which somewhat replaces the end of the staged version in the classroom, doesn’t support the unfolding plot. The primary issue, even if the added time is only a couple of minutes, is it sets up a false promise. Madam Morrible gives the impression that if Elphaba controls her emotions, it will enable her to make full use of her powers and thus allow her to meet the wizard. The problem this creates is that she next uses her powers when she gets mad at the caged lion demonstration. A scene identical to the play. After this demonstration, Madam Morrible writes to the Wizard, and he sends for her. There is no controlling her emotions to gain mastery of her powers, and this is ultimately not how she meets the wizard. It’s the exact opposite.

This scene doesn’t help to create good payoffs in the end and is one of the aspects of Elphaba’s arc in the film that feels unresolved. She never learns to control her powers, when she gets to Oz she simply knows how to read from the grimmerie and then she uses one spell. This scene could have helped set up her knowing how to read the text or added a little to the prophecy. Yet it decides to signpost themes it never explores again.

Difference two: dancing through life segment

In the play, this section runs for 00:14:41 versus 00:26:28 in the film. This extended sequence though doesn’t add any more plot. The elements of it are, more or less, unchanged. More scenery is chewed up with Fiyero interacting with minor characters, Dancing Through Life is staged a minute longer, and then there is the dance scene between Galinda and Elphaba, which is 0:06:31 in film time, double the length of the play.

In both the film and play, Elphaba embraces herself and, instead of getting mad or leaving, chooses to stay and do her dance. Galinda, because Elphaba has asked Ms. Moribble to teach her, joins Elphaba to lend her some social capital, and the other students join in. It’s a great moment, and it shows that Elphaba is growing into herself and possibly letting go of her desire to de-greenify, and it launches the friendship between Galinda and Elphaba.

If we look at the Elphaba/Galinda dance scene from the standpoint of the movie’s running time, it ends at 01:16:00, almost exactly the film’s midpoint. In general story structure, the midpoint tends to be a false victory or false defeat and shows progress for both the A and B plots.

Contrast this to the play, where the dance scene ends 45 minutes in. It is not the midpoint, it’s part of the ‘Fun and Games’ beat. In the staged version (for reference, the film ends at the midpoint), which makes a lot more sense from a plot structure standpoint. Because the film’s midpoint is the dance scene, it focuses the audience’s attention on the Elphaba/Galinda relationship and not the animal freedom or Elphaba’s powers. This doesn’t flow with Madam Morrible’s added scene and the idea of harnessing her powers.

The fragmentation of story

With the film’s climax being the story’s midpoint, where does this leave Elphaba and Galinda, our main characters? Elphaba’s false victory of meeting the wizard is the culmination of what she’s wanted “since birth.” This quickly fizzles when she learns that he doesn’t possess any magical abilities and is behind the imprisonment of the animals. Elphaba discovers that she possesses magic and is the person of prophecy who can read the grimmerie. However, this talent has nothing to do with her studies or ability to control her anger / personal growth.

This tends to be one of the issues with the ‘chosen one’ troupe in fantasy. Given that this is a chosen one story, it’s forgivable from a plot/narrative perspective, but it doesn’t solidify the character arc of the film we’re watching.

Galinda, on the other hand, tagged along to Oz. She isn’t super bothered by the Wizard’s heal turn (a reinforcement or her performative allyship) and tells Elphaba if they bend a knee, they can have what they want. It’s a betrayal of the friendship they’ve built throughout the story, and it acts as a great bookend for the Elphaba / Galinda arc.

And yet, because the film doesn’t use its runtime to enhance this relationship, it doesn’t feel like the plot’s climax. It doesn’t feel like a conclusion to the character arcs. Elphaba has given up on her desire to de-greenify; she only wants to help the animals. She has grown. Galinda, on the other hand, is self-serving throughout the film; she doesn’t have her growth moment. And so, when she decides to stay, it seems more aligned with the character we know than a step backward. A couple more scenes between Galinda and Elphaba to solidify their friendship would have helped solidify this arc. It’s an arc that doesn’t feel out of place in the play’s breakneck pace, but in the film, these characters need more time to create a deeper connection.

The ‘young Elphaba’ example proves the effectiveness of a minute and a half; these don’t have to be long, drawn-out sequences. Then when Elphaba offers for Galinda to flee Oz with her, Galinda could think about it, it’s a temptation for her to be powerful and magical. It’s what she started out wanting. And this conveys the internal struggle between magical power and being likable. Or unpopular, the antithesis of her anthem. She cannot change, even as Elphaba has grown past the need for others validation, she will not “play by the rules of someone’s game.”

On the side of, while the shedding of her need for approval works within the elements present throughout the film, it lacks the triumph for an effective climax. On the other hand, freeing Dr. Dillmond from Oz (a plot element in Act II) with her newfound abilities thanks to controlling her emotions (or better, channeling them instead, showing her remarkable empathy that is the true power), this might have worked as the climax for this film. After she freed Dr Dillmond, she could elude to never resting until every animal in Oz is free. A setup for the second movie allows a satisfying conclusion to this film. It resolves the Dr. Dillmond storyline, connects to the theme of controlling/feeling emotions, makes the betrayal by Galinda more potent because their relationship is more substantial, and allows the second film to expand further as Elphaba steps into her new role as Wicked.

Part I: song for song

Another area to note: there are no additional songs, with the minor caveat of an extended version of ‘One Short Day.’ In analyzing the difference between the staged and film versions, the film songs tend to be longer than the staged versions, per the table below.

The times in the picture above are approximate from the actual lengths of the performances. One item to note, in both No One Mourns The Wicked and Defying Gravity, I’ve used the official soundtrack times as these both contain extended sequences of non-singing, which add more to runtime than the actual songs themselves. It makes it a more apt comparison of the song-to-song length instead of staging/action-beat directions. There is a little bit of Jeff Goldblum hamming it up and stealing screen time in Sentimental Man, but we’ll forgive him.

With this in mind, besides the added song section of info-dumping backstory on the grimmerie in the middle of One Short Day, there are no additional plot elements from the excess time. The lyrics are identical, and there is no more emotion or character development than in the play. For instance, the extra minute of popularity reveals nothing more about Galinda. The excess staging, while campy and helping to set the film’s tone, doesn’t amplify the characters themselves. The film doesn’t have to be as expeditious as the play, but these little time segments add up.

Only a fraction of the additional time represents lengthening the musical numbers. It makes sense. Other than changing the tempo or adding in more dance flourishes or camera angles/trickery, there isn’t much they could have added with the songs unless they’d chosen to write new material, which is honestly shocking they didn’t. One more song, helping to establish the relationship between Galinda and Elphaba, might have played well with their overall arc of Part I, as noted above.

The fragility of part I

Ultimately, the director and writers of Wicked Part I chose not to modify the play’s structure, whether to ensure the loyalty of die-hard fans or to veneration the original. Either way, they did a disservice to the story by lengthening the runtime without ensuring it reinforces the plot of the film they’re actually making. How many people will watch Part I and Part II in one sitting? That’s five hours of movie to get a complete story arc.

In a play, there is the intermission, we get to talk with friends about what happened, what we liked, what we think will happen in Act II. We sip a rather forgettable Pinot Grigio and then return for Act II. With the film, it’s another year before the release of Part II. Instead of feeling like a complete episode of a duology, it truly is Part I. It is incomplete, and when we walk out of the theaters, defying gravity stuck in our heads but feeling somewhat beleaguered by a film that seemed lopsided, it is because they did not craft this film to stand on its own. And I do not have the pleasure of a short intermission before Act II begins.